How our current approach to science pushes people away

The current system of academic science is not organized to support all scientists equally.

“I’d found out that if you pushed people away hard enough, they tended to go.”

― Morgan Matson, Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour

Despite efforts to promote under-represented demographics within academic science, stark opportunity and outcome disparities persist. The causes are systemic and supported by ample evidence, and it’s important that we reflect on their repercussions.

Humans self-identify into thousands of overlapping ethnicities, multiple genders, and various socio-economic classes; the fluid boundaries between categories are not always possible to define, can change based on perspective, context, and over time, and are sometimes arbitrary. The idea that any subset of researchers has more to offer the scientific community than others ignores nearly 5,000 years of documented history showcasing scientific breakthroughs arising from diverse people from every major region of the world. Preventing certain scientists from participating on an equal footing with their peers by denying them equal access to career advancement opportunities, resources, and platforms robs us of the collective ingenuity that our diversity offers.

Before our systems of scientific training can be reformed, we must acknowledge that the status quo allows implicit and institutional bias to affect career advancement.

For example:

2019 UNESCO Institute for Statistics data showed that while women comprise 50 percent of the human population they account for fewer than 30 percent of the world’s researchers.

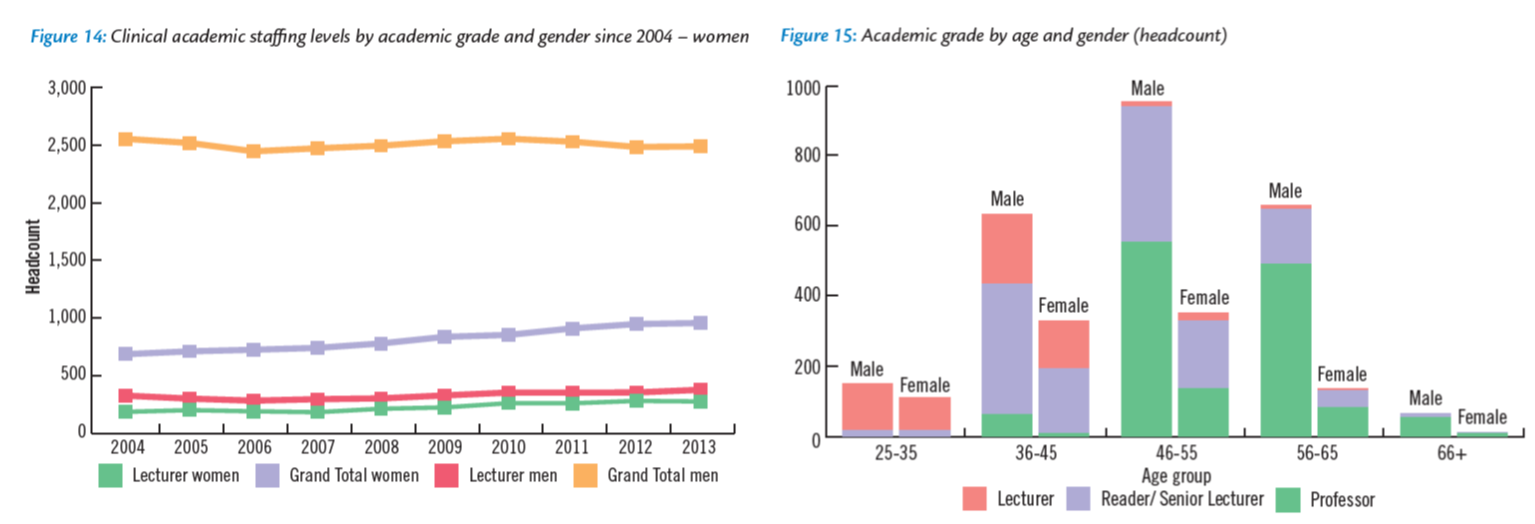

A 2014 survey by the Medical Schools Council in the U.K. found that while 44.5 percent of U.K. academics in 2013 were women, only 20 percent of professors were women.

A 2011 study by Ginther el al. showed that African-American/Black applicants were 10 percent less likely than white scientists to receive an R01 award from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, even after controlling for educational background, country of origin, training, previous research awards, and employer characteristics. Similarly, a 2016 study by Ginther el al. showed that Asian and Black women with PhDs, and Black women with MDs, were similarly less likely to receive NIH R01 funding compared with white women with the same qualifications.

A 2019 study by Hoppe et al. examining the individual stages of the R01 grant application process found that applicant race accounted for disparate outcomes. Notably, African-American/Black applicants tended to propose research on topics with lower award rates. These topics included research at the community and population level, as opposed to more fundamental and mechanistic investigations, which tended to have higher award rates. Topic choice alone accounted for over 20 percent of the funding gap after controlling for multiple variables, including the applicant’s prior achievements – illustrating how implicit biases can impoverish science by decreasing the diversity of topics and approaches.

The current system of academic science is not organized to support all scientists equally, in ways that push many young scientists away and rob us of their talents, innovations, and accomplishments. It is important that we recognize this reality and assume responsibility. While many of the systemic societal issues that contribute to this bias are not under our direct control, we must assume responsibility for those that are, such as recruitment and hiring, administration of grants, review and publication of great research, and promotion of scientific talent.

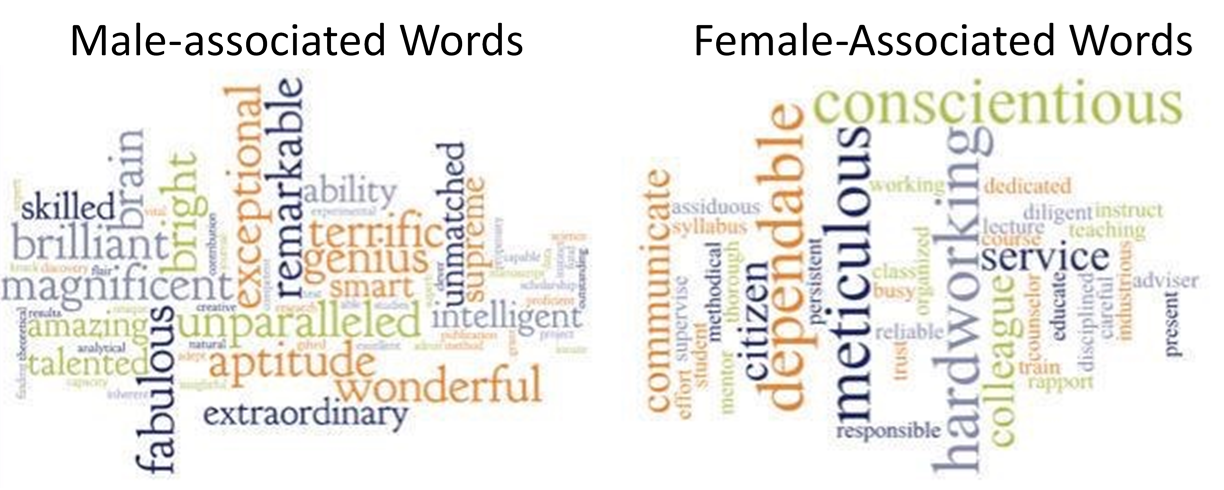

Much of this behaviour is driven subconsciously by implicit bias – judgments and/or behaviours that result from subtle cognitive processes (e.g. attitudes and stereotypes) that often operate below our conscious awareness and without intentional control. An individual is assessed more positively if they belong to a group that is stereotyped as being good at the task in question, and more negatively if they belong to a group that is stereotyped as being bad at the task in question. All of us operate with some level of implicit bias, which is heavily influenced by our culture, experience, and upbringing.

In my next column we’ll think through some examples of how we can identify implicit bias in scientific training, and practices we can implement to correct their effect.

If you are curious about your own implicit biases, Harvard has created an Implicit Association Test that is fun and illuminating to take.

Featured Jobs

- Education - (2) Assistant or Associate Professors, Teaching Scholars (Educational Leadership)Western University

- Business – Lecturer or Assistant Professor, 2-year term (Strategic Management) McMaster University

- Psychology - Assistant Professor (Speech-Language Pathology)University of Victoria

- Canada Excellence Research Chair in Computational Social Science, AI, and Democracy (Associate or Full Professor)McGill University

- Veterinary Medicine - Faculty Position (Large Animal Internal Medicine) University of Saskatchewan

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.