Ontario: The new pragmatism

After a decade marked by funding cutbacks and a tuition freeze, the province’s universities face the future with an eye for opportunities.

They threw a party for Laurentian University last June.

About 200 academic, business and political VIPs from the northern Ontario city of Sudbury raised glasses at the local reception, held in the industrial-chic headquarters of the homegrown Technica Mining company, where gold-and-white balloons rose toward the rafters. Hosted by the company’s founder and CEO, Mario Grossi, and by Michael Di Brina, co-founder and president of the financial planning company Gold Leaf (both Laurentian alumni), the glittery event was a “gesture of confidence in Laurentian’s future, in its leadership and its profound value to our community,” said master of ceremonies David Di Brina, a managing partner at Gold Leaf and Michael’s son.

The celebratory mood was a welcome change from the aura of despair that enveloped Laurentian in February 2021, when it became the first and only public university in Canada to declare insolvency under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act. The university abruptly cancelled dozens of programs, eliminated nearly a quarter of its faculty and staff, and discontinued its federation with three smaller universities, Huntington, Thornloe and Université de Sudbury. The action also led to a plunge in enrolment and a hard look not only at what had gone wrong at Laurentian — Ontario’s auditor general found that ill-advised capital expansion and weak governance were mostly to blame, exacerbated by provincially mandated tuition cuts — but also what might go wrong at other universities.

Four years of painful restructuring, government intervention and leadership change later, things are turning around for the mid-sized, bilingual university. Admission confirmations from Ontario high school students in June 2025 were up more than 23 percent over the previous year, though still lower than numbers in the late 2010s. And while Laurentian formally exited bankruptcy protection in late 2022, it was still wrapping up sales of some of its real estate to the province this past summer, intended to help pay off its creditors. Billing itself “Canada’s mining university” in a city built on mineral extraction, Laurentian aims to be part of the Ontario government’s ambitions to develop the province’s critical minerals industry.

“We are excited about the future,” says Lynn Wells, who became Laurentian’s president in April 2024. “People actually stop me on the street and say, ‘Hey, you’re the president of Laurentian. I hear things are going really great there now.’ And you know, that’s an amazing feeling.”

After Laurentian declared bankruptcy, the law was changed to prevent other publicly funded universities from doing the same. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t faced similar financial struggles. The past decade has been hard on Ontario universities: a litany of funding shortfalls, budget deficits and cuts to staff, faculty and programs. In response, the institutions have adopted survival tactics, including partnerships with industries, ambitious donor campaigns, and lobbying efforts intending to prove their worth to the provincial government.

A decade of scrimping

Ontario universities’ money problems go back to at least 2017, when the provincial Liberal government effectively froze the number of domestic students for which each university would receive per-capita funding, which was also frozen. The situation worsened in 2019, when Conservative Premier Doug Ford cut tuition fees for domestic students by 10 per cent and left them there, while maintaining the funding freeze.

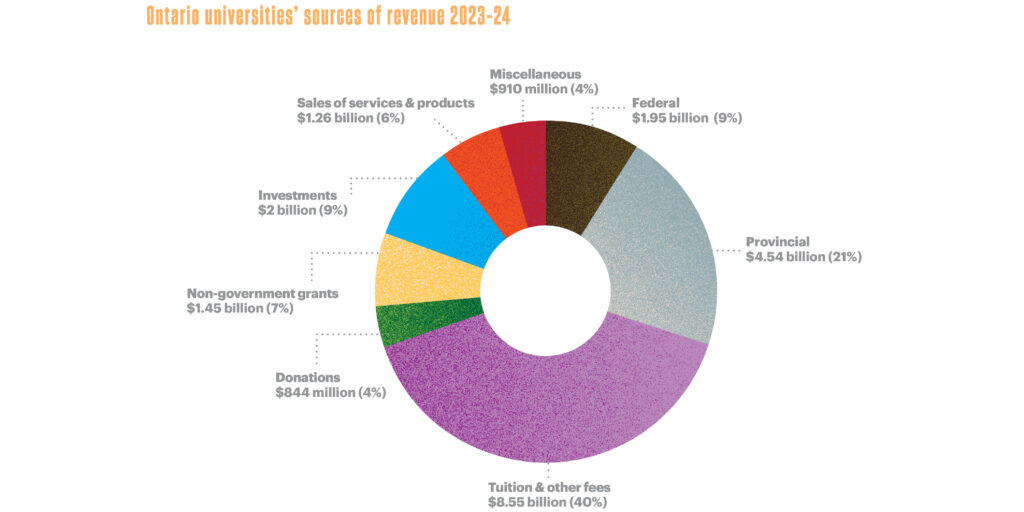

In 2023, a provincially appointed blue ribbon panel found that Ontario provided its universities with only 57 per cent as much funding per student as the Canadian average. The panel’s report called for an immediate five per cent tuition increase and a 10 per cent increase in base funding, with minimum two-per-cent increases annually for three to five years thereafter to compensate for the original cuts and for inflation. This did not happen.

Then in January 2024, amid a housing and social services crisis, the federal government cut the number of international student visas by 35 per cent, followed by another 10 per cent in 2025. The blow arguably hit Ontario hardest, with its universities facing a total $900-million revenue loss over the 2024-25 and 2025-26 academic years, estimated the Council of Ontario Universities (COU).

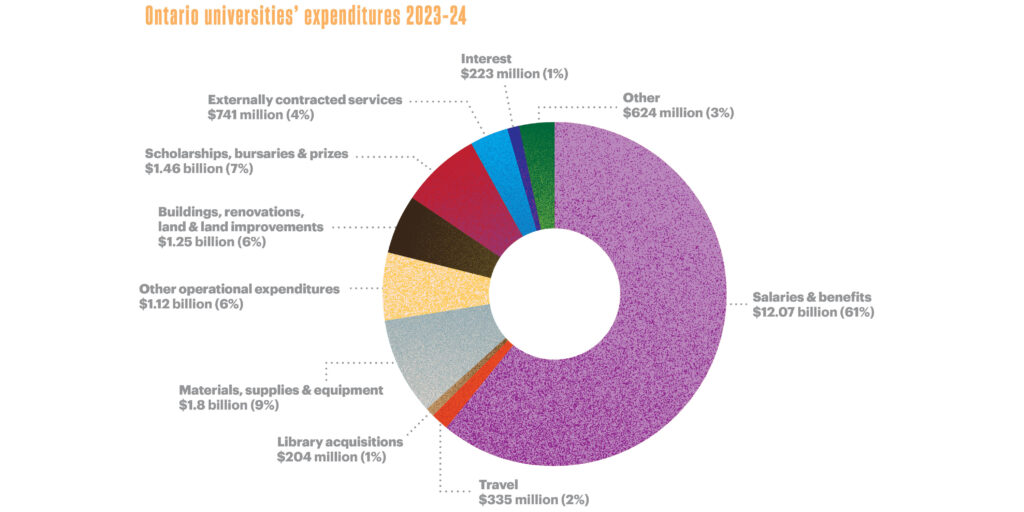

Some 17 out of Ontario’s 24 universities are, or have been, under government mandated third-party efficiency reviews, and many are dealing with deficits and related cuts to programs, faculty and staff. Among them, Carleton University in Ottawa projected a $32-million operating deficit for 2025-26, Queen’s University in Kingston a $26.4-million deficit, and the University of Waterloo a $44-million structural operating deficit. Universities have “passed the part of scraping things off the bone to make things more efficient,” says Nigmendra Narain, past president of the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA) and a political science lecturer at Western University in London. “We’re into the hacking of the bone.”

Seizing the “Canada Strong” moment

But after all the bruising and battering, universities have found ways to adapt, and some are emerging in fighting form. Amid the trade wars with the U.S., political leaders are determined to make Ontario, and Canada, less reliant on our southern neighbours. Universities argue that they can support the government’s priorities through research, education and training in such areas as critical minerals, advanced manufacturing, nuclear power and life sciences.

“I think the threats from the U.S. have really galvanized business support for higher education and also have given the government a renewed sense of investing in key aspects of university activity, which is important to the talent pipeline,” says Steve Orsini, COU’s president and CEO. Mr. Orsini has penned joint letters with business leaders urging the province to increase financial support to universities, and big-city mayors have called on the province to implement the blue ribbon panel’s funding recommendations.

The province announced in early 2024 a $1.28-billion boost to the postsecondary sector over three years. And in spring 2025, Minister of Colleges, Universities, Research Excellence and Security Nolan Quinn announced another $150 million per year for five years to fund 20,500 seats in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Mr. Quinn said his government was “working to protect Ontario by building a more resilient economy.” Another $55.8 million was earmarked to train up to 2,600 new teachers by 2027. Base funding remains the same, though.

Among the universities capitalizing on the province’s economic ambitions is Oshawa-based Ontario Tech, an institution with some 11,000 students founded in 2003. Located near two of Ontario’s three nuclear power plants, the university has been selling curricula and other educational intellectual property from its signature nuclear engineering programs to other jurisdictions including Alberta and Saskatchewan. The university has also signed IP agreements in southeast Asia and eastern Europe. “We’re going great guns there,” says president Steven Murphy. “It’s really a phenomenal time for us.”

Projecting a $3-million surplus for the coming year, Ontario Tech was among four Ontario universities that came under the auditor general’s microscope in 2022 for below-average financial performance. It has since implemented or is implementing the recommendations from that process, while identifying new revenue and education opportunities, such as graduate diplomas and a nuclear career accelerator program in collaboration with government, aimed at upgrading engineers and other professionals in nuclear-specific skills.

While nobody should be “thinking that universities can solve all their own problems,” and they require government support for teaching and basic research, there are still opportunities for them to develop stronger partnerships with industry that can yield revenue, experiences for graduate students and a chance to share and develop research, says Alison Symington, chair of Life Sciences Ontario, an industry advocacy group. U of T’s Acceleration Consortium is one example, she says, where academia, industry and government work together to develop advanced eco-friendly materials more quickly and at a lower cost.

“I’m not sure all the universities across the province have quite got their head around the institutional partnerships and what they could look like and how to make it always a win-win,” says Dr. Symington.

Hard times for the humanities

In an era where government’s priority is STEM, whither everything else?

Queen’s University, with its $26.4-million operating deficit, has frozen hiring and is moving towards department amalgamation in its arts and science faculty — particularly hard-hit by the loss of international students — along with bigger class sizes and elimination of small-enrolment courses. Daryn Lehoux, a philosophy professor and head of the Department of Classics and Archaeology, says small classes occur in the humanities and fine arts as well as the sciences, and he’s skeptical their cancellation saves any significant money. His department managed to temporarily stave off an early 2024 faculty directive that courses with chronically fewer than 10 students would be cut, which would have eliminated most upper-year classics courses in ancient Greek and Latin — a potential death blow for the discipline. But Dr. Lehoux only has until 2027 to get the numbers over that threshold.

“We’re still carrying on,” he says. But combined with other difficulties such as marketing the classics to students with no prior experience of them, “this is a major problem … It just feels like we keep getting kicked when we’re down. The morale is terrible right now among faculty members, among staff.”

Mr. Narain of OCUFA argues that even the professional programs favoured by government need a pipeline of humanities and other basic subjects to feed them. The provincial government’s additional funding for teacher education is great, but, “Where do most of the teachers come from?” he says. “Well, they come from biology classes, math classes, history classes, English classes, French classes.”

Many students continue to show their passion for arts and humanities. Applications to OCAD University in Toronto, with its art and design focus, were up nearly 25 percent in 2025 compared to 2024 — from 2,115 to 2,637. Huron University, a predominantly undergraduate liberal arts school affiliated with Western University in London, with an enrolment of roughly 2,100 students and an average class size of 30, saw a similar increase. Its president, Barry Craig, partly attributes that to students’ craving for human interaction after COVID-19’s grim Zoom years: “To come to a small community where your prof knows your name, where you see each other, and you have that human connection, I think that’s one of the things that’s drawn people to this model.”

For more than a decade, Ontario governments have asserted increasing involvement in universities. Strategic mandate agreements, encouraging colleges and universities to focus on strengths and eliminate unnecessary program duplication through performance-based funding, were introduced by the Liberal government in 2014. The Conservative government went further with plans to tie a higher proportion of funding to performance on specified targets for skills and jobs outcomes and economic and community impact. That plan was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the government reduced the proportion of funding that would be tied to performance.

The provincial government has also drawn complaints of interfering with university autonomy: In May 2024 it passed Bill 166, giving it authority over postsecondary institutions’ policies on mental health, anti-racism and hate. Then, in May 2025, it introduced Bill 33, which directs postsecondary institutions to admit students based on “merit” and gives the province powers in the approval of student ancillary fees. Minister Quinn’s press secretary, Bianca Giacoboni, said in an email that no regulations around Bill 33 will be made until sector consultations are concluded, and that it is intended to enhance transparency and trust in the postsecondary system.

French remains fragile

With their typically smaller classes and programs, French-language higher education institutions in Ontario have been particularly vulnerable in the current climate, especially after Laurentian declared insolvency and severed its federated relationship with Université de Sudbury and affiliate Université de Hearst. The unilingually francophone Hearst became a standalone university in 2022, Université de Sudbury struggled for provincial funding until an agreement allowed it to run French-language programs in partnership with the University of Ottawa starting in the fall of 2025 (the blue ribbon panel recommended smaller French language post-secondaries strike up similar partnerships to ensure their viability).

After almost failing to get off the ground when the Conservative government initially cancelled its funding in 2018, l’Université de l’Ontario français (UOF) in Toronto took in its first undergraduate students in fall 2021. Its startup has been backed with $126 million in combined provincial and federal money, spread over eight years until 2027. Its enrolment sat at 360 in 2024-25, and is expected to grow to 570 for 2025-26. The bachelor of education program is its most popular option in an era of French-language teacher shortages, with 240 new students admitted this fall. Cuts to international students, who make up 20 per cent of the student body, have created a financial challenge, says president Normand Labrie: “Two years from now, we will be funded like any other university and the challenge will be at that time to continue the growth with resources based on current student numbers.”

The way forward

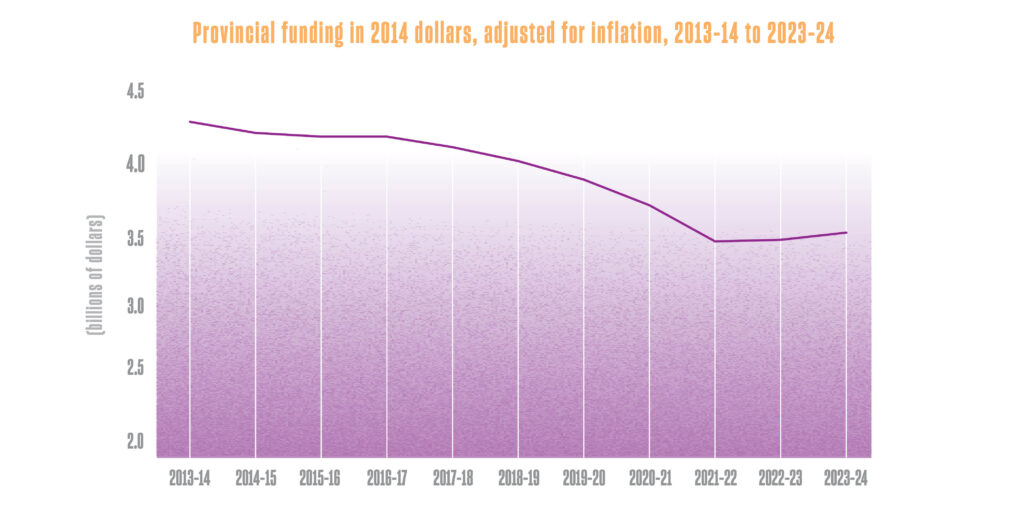

Newly released data from Statistics Canada show that, in 2023-24, Ontario’s funding for universities increased in real dollars for the first time in years. Adjusting for inflation, the increase amounted to 1.2 per cent, “a notable change following a decade of declines,” the StatCan press release said. StatCan has not yet crunched the numbers for 2024-25, so its data doesn’t include new funding in Ontario’s 2025 budget.

“At the very best you can say that the province has thrown a little bit more money at the system but it still isn’t catching up with where it should be,” says Glen Jones, a professor of higher education and former dean at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at U of T, in reference to the 2025 provincial budget. “There’s a lot of angst and challenging political decisions that leadership at many universities are trying to navigate and there’s no easy solution to it other than the notion of trying to find additional revenue, which we know is not an easy solution to find.”

As Ontario universities begin the 2025-2026 year with new five-year strategic management agreements, the provincial government has been reviewing its postsecondary funding model. Ms. Giacoboni of Minister Quinn’s office insisted that “the tuition freeze remains fully in place,” although a Toronto Star report suggested the government may consider lifting it. University presidents have sounded more hopeful about that, than about any serious increase in long-term base funding.

Rather than relying on government, there is a sense that new models will have to come.

More collaboration among postsecondary institutions offers one way forward, suggests Dr. Wells of Laurentian. In addition to community and industry partnerships, Laurentian is partnering with local colleges and other northern Ontario universities on learning pathways and research. “I was in Western Canada for a long time,” she says. “And in the West, collaboration among post-secondaries is just the way things are done. To be honest, I was surprised when I came back to Ontario after 20-plus years to find that it wasn’t kind of an automatic way of doing things.”

Fundraising is another important source of revenue. In 2021, U of T launched its Defy Gravity campaign, aiming to raise $4 billion for priorities such as sustainability, health, scientific discovery and entrepreneurship. That’s an inspiration for Dr. Craig of Huron, as he seeks to keep offering small classes and a unique student-centred experience. “Philanthropy has to be a part of this,” he says. The university brought in a $10 million gift last winter from Fairfax Financial — headed by Prem Watsa, who has also been Huron’s chancellor since 2017 — and another $5 million from the Schulich Foundation.

Fundraising on this scale is new for Huron. But, says Dr. Craig, times have changed. “I think all of us are going to be looking for more,” he says. “We can say it shouldn’t be that way, we shouldn’t have to do it. Or, we can get on to do what we have to do.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the Minister of Colleges, Universities, Research Excellence and Security announced $750 million a year for five years to fund 20,500 seats in STEM. The funding amount is $150 million per year for five years.

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

1 Comments

Unfortunately, the $750 million investment from the province isn’t per year as written. It is $750 million over five years, or $150 million per year.

$750 million, which is above what the Blue-Ribbon Panel recommended for the first year, would be a very welcome investment.