Research re-imagined

As academics experiment with the graphic novel form, their research is reaching – and influencing – new audiences.

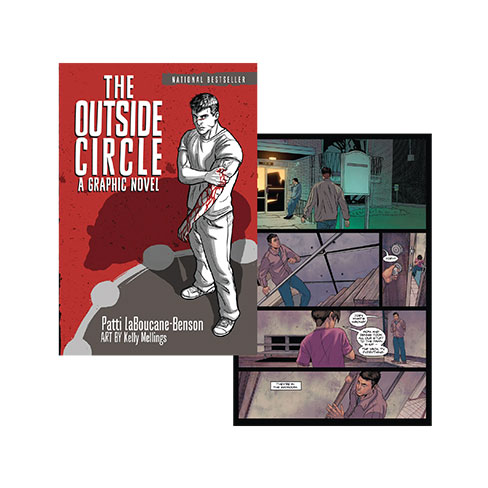

After successfully defending her PhD in human ecology in 2009, Patti LaBoucane-Benson was encouraged by her supervisory committee at the University of Alberta to publish her dissertation as a monograph.

She had a different idea. A voracious comic book reader, she envisioned her research – on how trauma-healing programs for Indigenous offenders build resilience in families and communities – taking the form of a graphic novel.

“I wanted to talk to everyday Canadians about what I had learned, and about the reality of what historic trauma is and what we need to do to heal,” says Dr. LaBoucane-Benson, who was appointed to the Senate of Canada in 2018. “I wanted to push that message out to a broader population.”

She reached out to Edmonton illustrator Kelly Mellings and the two went on to reimagine her research as a piece of creative non-fiction, publishing The Outside Circle with House of Anansi Press in 2015. The graphic novel, which also includes the work of artists Allen Benson and Greg Miller, is about two Indigenous brothers trying to overcome centuries of historic trauma, and is an award-winning bestseller.

More academics are recognizing the power of the graphic novel medium to communicate their findings to a broader audience and to engage with readers much differently than they would through peer-reviewed articles and academic books. Some are publishing their PhD dissertations as graphic novels, even using them to replace a traditional thesis, while others are developing fictional stories based on their research, or integrating comics as tools in their research process.

What exactly is a graphic novel?

Through text and illustrations, graphic novels tell stories. They’re similar to comic books but differ in length; graphic novels are typically longer and contain complete stories instead of serialized narratives.

Dr. LaBoucane-Benson, who is Métis, describes being able to share her research in this untraditional format as “amazing.” Just as she had hoped, the graphic novel form allowed her to reach a broader audience. Her book is used in junior high, high school and university classrooms. It’s a heavy and layered story, yet also so readable that it can be completed in one sitting. Dr. LaBoucane-Benson recounts a visit to a school in northern Alberta where she spoke to a Grade 10 class of primarily Indigenous students. The boys who had been labelled as reluctant or resistant readers were the first to finish the novel. They identified with the characters, she says, which led them to ask the hardest questions.

The story has also reached many readers outside classrooms. “I think that the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is transforming as we speak, but we still have a lot of work to do, and I find the graphic novel is a powerful tool to engage in those conversations,” Dr. LaBoucane-Benson says.

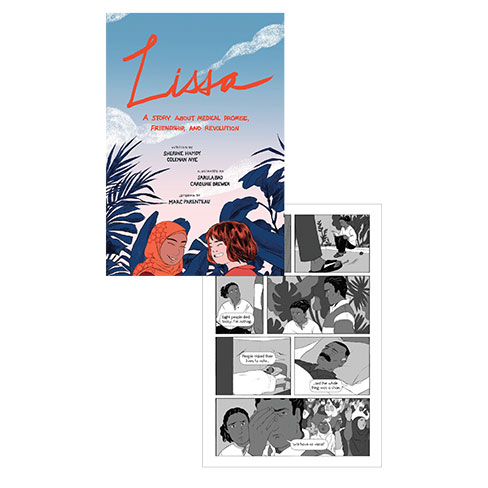

Coleman Nye, an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University’s department of gender, sexuality and women’s studies, also understands the immense potential of this format. “There’s so much that these stories can communicate with a combination of text and images that you just don’t get across with text alone,” says Dr. Nye, who is currently working on a book for academics about how to incorporate comics into research.

Dr. Nye is the co-author of the graphic novel Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution. Published in 2017, Lissa was “a big experiment,” Dr. Nye says, and the debut graphic novel in the University of Toronto Press’s (UTP) ethnoGRAPHIC series, which adapts ethnography into comics. The book tells the story of an unlikely friendship between two young women who go on to face major medical decisions against the backdrop of Egypt’s Arab Spring.

The project started at Brown University as Dr. Nye, then a PhD student researching cancer genetics, and co-author Sherine Hamdy, a professor examining organ transplants in Egypt, looked for ways to collaborate. Both were familiar with the field of graphic medicine in which comics are used in medical education and patient care. Dr. Nye found that any comics-based storytelling she shared in her medical anthropology courses resonated deeply with students. “There’s a lot of reader participation and imagination that goes into the comic page,” she says, adding that the lightness of comics can also make it easier to access particularly difficult subject matter.

They decided a graphic novel was the ideal way to combine their work on very different medical decisions while permitting them to delve into the similarities (such as how a patient’s experience with illness and treatment is deeply shaped by social, political and environmental contexts).

“In a piece of text, you have to read line by line – it’s linear. In a comic, the page is a world,” Dr. Nye says. “You can combine and juxtapose and layer different times and places and experiences and perspectives, all into the same page even. The possibilities are really exciting.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Hamdy began by writing a piece of fiction based on their research. They then reached out to the nearby Rhode Island School of Design and connected with student-illustrators Caroline Brewer and Sarula Bao. The team also brought on visual editor Marc Parenteau, who helped them understand the intricacies of creating comics, from paring down dialogue to rethinking pacing.

Lissa’s authors decided to share the details of their publishing experience and advice to interested academics through a website, a documentary and several appendices in the book. They contend that the benefits of illustrated scholarship are plentiful, from protecting the identities of research participants to bridging disciplines. “Comics allowed us to do so much,” Dr. Nye says. “It’s remarkable.”

Lissa is now taught in different courses at universities around the world, including in classes on medical anthropology and the Middle East. UTP, meanwhile, will publish the seventh book in its ethnoGRAPHIC series this June, a book called Forecasts: A Story of Weather and Finance at the Edge of Disaster written by Caroline E. Schuster. Carli Hansen is acquisitions editor for anthropology and sociology at UTP, and manages the ethnoGRAPHIC series. She’s seen first-hand how graphic novels make research more accessible: “That might mean students, it might mean general readers here in Canada and the U.S., it might mean people in the community where the research was done who wouldn’t be able to read an academic monograph, but they might read a graphic novel,” she says.

Ms. Hansen explains that the books are usually collaborative global projects involving an academic in Canada or the U.S. writing the story based on fieldwork done in another country, and a freelance artist who is often based in the country where the research takes place. While rich in creative potential, navigating those relationships, time zones and the academic publishing process can be complicated. “There’s been a lot of learning along the way and a lot of tweaks to our processes,” she says. “We learn something new from every project.”

Peer review has been one of those adapted aspects, with experts in the field vetting how effectively the research has been translated into the graphic format. While it can vary book to book, Ms. Hansen says most projects are first peer reviewed as a written proposal with a sample from the artist. Later, a full manuscript review is done based on storyboards or other rough drafts of the art.

For Dr. Nye, that process was one of the biggest challenges. “The really hard thing about making comic pages is that it’s so much work to revise them,” she says. “It’s not like a Word document.”

In the English department at the University of Calgary, Jamie Michaels is working on a graphic novel for his PhD. His research focuses on nationalism and the role that Jewish and Arab soldiers played during the First World War supporting the British against the Ottoman Empire. “I come from a Jewish background, I have friends and family in Israel, I also have close friends in Palestine,” he says. “I think it’s really important to bridge a gap I was seeing … and maybe expand the historical breadth through which we understand each other.”

Mr. Michaels describes himself as a “big nerd” who grew up making lighthearted comics as a kid. He founded Dirty Water Comics in 2016, a Winnipeg-based publisher of graphic novels, including his own book, Christie Pits, that’s being adapted for film. As a scholar, he’s exploring the form’s academic potential. He points to A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, published in 1978 by Will Eisner, and Maus, about the Holocaust experience of author Art Spiegelman’s father, serialized in the 1980s, as works with staying power that display great empathy and change the way readers see the world. “I think this is a really dynamic form to ask people to consider, or perhaps to reconsider, history,” he says.

Comics are collaborative by their very nature, Mr. Michaels points out, which might explain why they are so engaging. “In a graphic novel, in that space between panels, the emphasis is back to the reader,” he says. “The reader infers the action between the panels in a way that’s unlike other forms.”

Like Mr. Michaels, Emanuelle Dufour used graphic storytelling as a primary presentation medium for her PhD dissertation. Her comics also became a research tool – “the main engine,” she says – for what would eventually become « C’est le Québec qui est né dans mon pays! » Carnet de rencontres, d’Ani Kuni à Kiuna. Published by Écosociété, the graphic novel focuses on Indigenous and non-Indigenous realities and relations in Quebec.

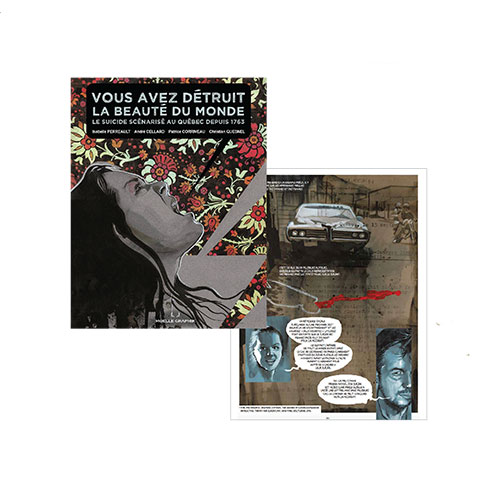

Turning complex and grim stories into accessible and understandable reads requires a simplicity that is not simple to achieve, says Christian Quesnel. He refers to himself as a “sequential artist” (a more precise term than illustrator). He is also a PhD student at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, where he teaches students how to make comics. Despite the challenge, he believes that comics are the best form to handle such heavy subjects, given their capacity to convey sensitive stories with respect and dignity. “The power of this medium is evocation,” he says. “It’s to tell a story without showing everything.”

University of Ottawa professors reached out to Mr. Quesnel to illustrate a graphic novel about the history of suicide in Quebec, Vous avez détruit la beauté du monde: le suicide scénarisé au Québec depuis 1763, published in 2020 by Moelle Graphique. He later worked on a graphic novel about the Lac-Mégantic rail disaster, Mégantic: Un train dans la nuit, by Anne-Marie Saint-Cerny, published by Écosociété in 2021. In both books, he was completely free to make the illustrations. “They sent me the text, dialogue, stuff like that, but there was no indication about images,” he says. Another graphic novel covering a harrowing subject is But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust, published last year by New Jewish Press, a UTP imprint. Acquisitions editor Natalie Fingerhut became involved after she read a newspaper story detailing work by Charlotte Schallié at the University of Victoria to bring together artists and Holocaust survivors on three continents and tell the survivors’ stories through the graphic novel medium.

She had a dim view of graphic novels before she started working on the project, she says. But when Ms. Fingerhut read the collected stories, her view abruptly changed. “The last story in the collection just put a knife through my heart,” she says. “I studied the Holocaust, and I’ve seen and read most of the hard-hitting literature. I saw this story, and it just floored me in a way that I had not been floored before.”

Ms. Fingerhut went on to help the project team of eight build the three stories into a book, a process that included fine-tuning the text and art, adding historical essays around the stories and sharing messages to the readers from the survivors. The aim was to make a book accessible to high school and university students, as well as to the general public. In fact, the idea for the project came from Dr. Schallié’s teenage son, who was resistant to reading, but had developed an interest in graphic novels.

The experience taught Ms. Fingerhut how powerful drawings can be. “Text can be dissociative, and the graphic [form] is not,” she says. She’s now working on more graphic novels about different genocides, and feels the format works particularly well for communicating tough subjects, especially to a younger audience. No matter the audience’s age, though, she sees the potential for impact.

“I think it hits you in a very different place than text [alone],” she says. “And I think if you allow it to do that, you come away more empathetic to what you’ve read.”

Post a comment

University Affairs moderates all comments according to the following guidelines. If approved, comments generally appear within one business day. We may republish particularly insightful remarks in our print edition or elsewhere.

2 Comments

What a great article ! Reading about all of those initiatives is very inspiring.

Along with 3 researchers (Maïa Neff, Romain Paumier and Pierre Nocérino), we are organising a 2 days conference (18-19 March) on the very issue of the collaboration between social sciences and the graphic novel medium called Planche la recherche, in Montreal. Artists and researchers have been inviting to discuss issues such as the collaboration between both professionals, the many ways to combine this medium with science making, edition of those hybrid production, etc.

We have also trained 8 couples of artists and researchers to these collaboration, which will result in the creation of a 4 pages graphic ‘novel’ based on their research.

There is much to be done and discussed to foster new collaboration, enrich the research done and reach new publics !

Thank you, Cailynn, for writing about these innovative examples of diverse knowledge engagement that have emerged from doctoral research across disciplines of study from across Canada!